Part 2 of 3 (Read Part 1 here).

When we reconvene, a woman named Pam takes the microphone from the governor and explains that she’s the chief facilitator from a Houston-based consulting firm and has made a career of working with community groups and businesses on conflict resolution, teamwork and overcoming mistrust. She has assembled a team of highly trained, volunteer facilitators from Kansas who will guide the group through something called “transformative scenario planning.”

It’s a five-step process that helps groups map out plausible scenarios so they can understand the consequences of their actions and get unstuck on a tough problem by together choosing a better path. Sounds touchy-feely and hard to get my head around, but, what the heck, I’m here. And they aren’t letting us out of here anytime soon.

They break the big group into smaller ones, made up of as diverse and contentious a mix of viewpoints as they can manage — which is how Kaye ends up in my group. Our discussions are usually pretty contentious, whether it’s about due process for teachers, drug testing for welfare recipients, judge selection or income taxes.

“That’s good,” I whisper to Kaye when I learn she’s in my group. “I already know what you think — and how wrong it is.”

Others in the group include, I soon learn, a free market advocate from southeast Kansas, an official from the state teachers’ union, a K-State professor, a Methodist pastor from Wichita and two school superintendents — one from a tiny district out near me, another from a good-sized one in a rich Kansas City suburb.

They assign each smaller group a referee — excuse me, facilitator — to keep us on track, which is good, because I fear we’re just wasting our time here. Greg, our facilitator, asks each of us to take a turn telling a bit about ourselves — where we’re from, what we do, whether we have kids in school — and what we think is a good education, as well as what we expect from the state in providing one.

Views and values start flying, and the little room gets warmer.

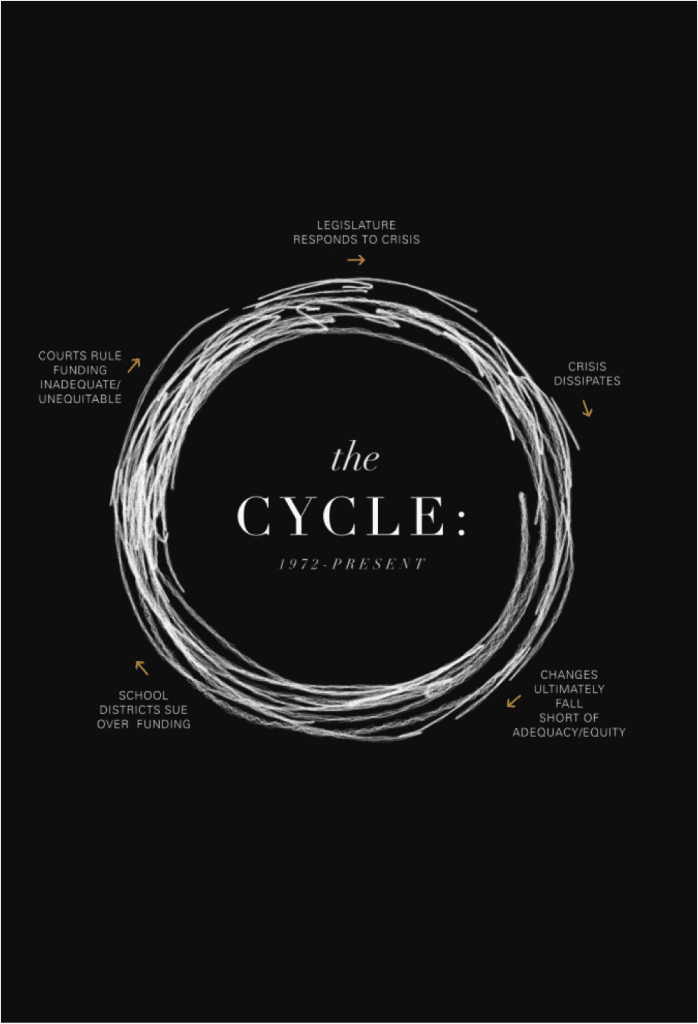

The union leader pipes in first — big surprise — with the spiel about how the Legislature hasn’t done its constitutional duty and is now picking on teachers, blaming them for a problem legislators and the governor created. Teachers and kids deserve better and now the courts will do what lawmakers resisted doing: force an increase in school funding and taxes. The small-government activist observes that as long as he’s been around, schools keep saying they want more money no matter how much they’re getting at the time. Times have been hard in his part of the state, and everybody’s got to share the pain when the budget’s tight.

“With lower income taxes the implement dealer can hire more people,” I toss out, “and jobs like that mean kids won’t leave my town for good.”

“But when your daughter goes to K-State, the tuition will bust even your bank,” Kaye counters, which gets me thinking about how, in a decade, four years at K-State or, God forbid, KU, will pinch even a somewhat successful small-town lawyer.

Hold up for a moment, Greg says, telling us that the discussion is descending into knee-jerk territory. He suggests we think carefully about the values that lie behind each of our positions.

Soon, we’re sinking deeper into defining what a suitable education is. I share that when I was on the school board, the administration always seemed to find money for new computers and smart screens and could pad the reserve fund, but my son’s math book is a decade old and his grade school class can’t take any field trips. Meanwhile, our school superintendent has the highest-paying job in the entire county.

The preacher from Wichita — his wife’s a special ed teacher — says the city’s district has thousands of kids with all kinds of problems that make it difficult to learn. Helping kids in poverty is expensive, and it seems like there are more in need every day. The schools there have so many programs that parents move to the district to get its services. That’s a big challenge with money so tight, the pastor says.

On top of that, he continues, the district has a tough time filling teaching jobs in areas like math and science, as well as in special ed. That may only get tougher with more baby-boomer teachers reaching retirement age and young people not seeing teaching as a viable, rewarding profession.

“I wonder if we’re on the verge of a crisis in terms of having enough qualified teachers to fill our classrooms,” the pastor says. “My daughter would have been a great teacher. But she found a job at Cerner, instead, and I have a hard time arguing with her choice.”

The challenges that teachers face in the classroom each day becomes a topic of conversation as well.

“I’d like it if my niece’s teacher didn’t have to corral 30 other 8-year-olds,” Kaye says, and I remember how my own kids’ elementary school can no longer afford an aide for that unusually big class, now fourth-graders, moving through the school.

Over the course of the next few hours, we start talking about the future and what it is we really want our school system to do for the kids of this state. Are we trying to get everyone to meet a minimum set of standards? Aim higher? What kind of education do kids really need to succeed in today’s world and how do we know if they’re getting it?

“I think what’s hard about this issue for me is that I just want someone to tell me the magic number for what we need to put in schools, whether it’s the court or some egghead’s cost study,” I say. “But I’m starting to think that magic number just doesn’t really exist.”

“And even if it did, all we’d do is argue about the number some more,” Kaye interjects. “Some people will think it’s too big, others too small. It’s always about how so-and-so didn’t figure this or account for that correctly. We fight about the number so much that we never get to the heart of the issue.”

“Or it’s just another round of the blame game,” the preacher joins in. “The Legislature failed. The schools are spending their money wrong. There are too many bad teachers. The voters can’t decide what they want — low taxes or well-funded schools. We can always turn a blind eye to how we’re adding to the mess by pinning the blame on somebody else.”

Bouncing what I’m hearing around in my own head, I’m struck by how deeply felt the opinions are, and how most of them are based on things we Kansans like to talk about — how important our cities and town are to us, how we want our kids to see a future in our communities. I remember hearing the same things from my neighbors last month when I asked about what they expected from the state, and what they’d give up, or pay, to get it. Striking, too, is that sitting and talking with these folks face to face makes it difficult to just write off their views.

It gets harder, though, when Greg tells us to consider the various plausible ways that the school-funding controversy may turn out and to consider the consequences. At first the scenarios sound mighty theoretical, but then Greg describes how the method has been used in situations far messier than this one, such as when South Africa ventured out of apartheid. With some guidance and questioning, we come up with a half-dozen scenarios but whittle them down to the three most likely ones.

End of Part 2. Stay tuned for Part 3.

Editor’s note: This description of a hypothetical process to resolve the Kansas school funding dispute is based on interviews with experts experienced in leadership, civic collaboration, public engagement and conflict resolution. It is informed by the techniques of fiction writing and the concept of transformative scenario planning, as described by writer Adam Kahane in a 2012 book on the subject.